Sunday, September 15, 2013

Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost

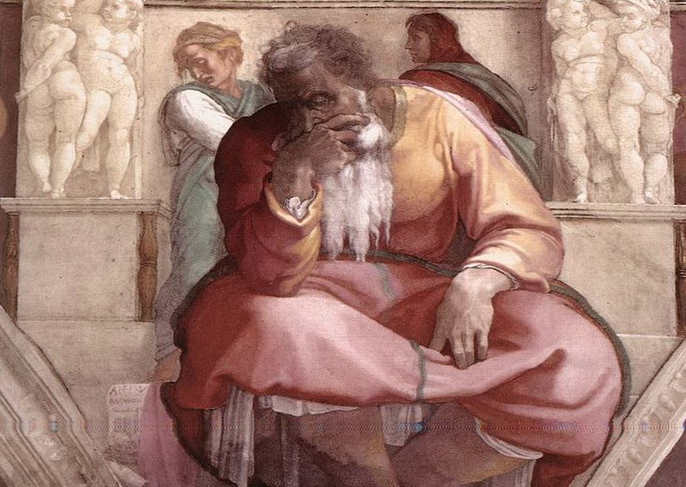

Jeremiah 4:11-12, 22-28

Rev. Dr. Amy Butler

_____________________________

* Due to technical difficulties during worship, there was no audio recording for this sermon.

An introduction to Jeremiah, modified from The Message:

“Imagine there was one guy on board the Titanic with sonar equipment trying to get the captain and crew to believe there was an iceberg ahead. They’d never heard of sonar and thought he was nuts. That guy was Jeremiah, and the Titanic was his country.

Jeremiah’s troubled life spanned one of the most troublesome periods in Hebrew history, the decades leading up to the fall of Jerusalem in 587 BC, followed by the Babylonian exile. Everything that could do wrong did go wrong. And Jeremiah was in the middle of all of it, sticking it out, praying and preaching, suffering and striving, writing and believing. He lived through crushing storms of hostility and furies of bitter doubt. Every muscle in his body was stretched to the limit by fatigue; every though in his mind was subjected to questioning; every feeling in his heart was put through fires of ridicule.

In a way, Jeremiah was a failure because he didn’t achieve the results he wanted. In a way, Jeremiah was a success, because he had the courage to tell the truth.”

I’m going to swear in this sermon. I mean, I’ll be quoting Tom Hanks when I do, but still.

I don’t want you all to be shocked, given the fact that I’m pretty sure none of you have ever heard me use colorful language. And, we are in church. But, honestly, I can’t really think of another topic on which using bad language might be more appropriate—how it feels to be out there on your own, all alone.

Today we’re continuing our consideration of the lectionary texts in the book of Jeremiah the prophet, thinking about the cost of being a prophet—the toll it takes to tell the truth.

There are, as we discussed a bit last week, lots of interesting angles to take when you’re studying the book of Jeremiah. There’s the historical perspective—the life of Jeremiah as presented in this book supposedly spans the decades leading up to, during, and after the fall of Jerusalem, when the Hebrew people were taken into exile in Babylon. Jeremiah’s prophetic career spanned the reigns of five kings, during a critical period in Hebrew history. For historical reasons alone, the book of Jeremiah is worth studying.

And then there’s a theological perspective—we could consider the way that God interacts with Jeremiah and with the people of Israel—to try to think about what we could learn about God from hearing this story.

There’s also a textual angle. There are all different kinds of writing in the book of Jeremiah. It’s chock full of beautiful language and colorful metaphor. And also, I’d note, some colorful language. That’s illustrated very well by the Jeremiah text for this morning, which is largely a poem. The book of Jeremiah is written using powerful images and haunting language.

But we’re not going to look at the text from any of those perspectives. Instead, we’re thinking about what it takes to tell the truth—the price that one pays to follow a call, to proclaim a difficult message, to live a life that stands in stark opposition to the prevailing opinions of society around you. Remember the definition of prophet we’re working with: prophets were called by God “to have an impact on persons, to impinge upon perception and awareness, to intrude upon public policy, and to evoke faithful and transformed behavior.”[1] Jeremiah was such a prophet, and he paid a steep price. Last week we talked about the price of following a call from God to the exclusion of other pursuits; this week it’s the feeling of being all alone. Totally, completely alone.

Listen to him: I looked on the earth, and lo, it was waste and void; and to the heavens, and they had no light. I looked on the mountains, and lo, they were quaking, and all the hills moved to and fro. I looked, and lo, there was no one at all, and all the birds of the air had fled. I looked, and lo, the fruitful land was a desert, and all its cities were laid in ruins before the LORD, before his fierce anger.

Jeremiah’s feel alone. All alone, and utterly desperate.

I never liked the ice breaker they seemed to do every single year at church youth camp. They’d make you get in small groups and you’d have to say the three things you would take with you if you were marooned on a desert island. Remember that? Supposedly this is supposed to help people get to know you? So, here’s the dilemma. You know that if you were really marooned on a desert island you’d probably want to bring something like matches, or a knife, or something to help you survive, right? Plus you definitely would want to take a picture of your boyfriend, and maybe lip some gloss? (High school, remember.)

The only thing is, you’re at church youth camp, so you have to include your Bible on the list, or else you don’t sound holy or Christian enough to everybody in your group. So I always hated that game, and I’ll just go ahead and admit that usually I would just list my Bible so I’d fit in with everybody else. And also because, of course I WOULD bring my Bible….

The only thing is, you’re at church youth camp, so you have to include your Bible on the list, or else you don’t sound holy or Christian enough to everybody in your group. So I always hated that game, and I’ll just go ahead and admit that usually I would just list my Bible so I’d fit in with everybody else. And also because, of course I WOULD bring my Bible….

I was thinking that’s the only thing I really know about being alone on a desert island, until I remembered Tom Hanks’ amazing 2007 movie, Cast Away. Just to refresh your memory, Tom Hanks’ character, Chuck Noland, is a Fed-Ex supervisor who travels all over the world for his job. On one trip the plane he is on crashes, leaving him stranded on an uninhabited desert island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. (Presumably without his Bible.) Tom Hanks is amazing in the film for the simple fact that most of the movie is about the four years he spends all alone on this island, thus there’s not all that much interplay between characters.

Of course the whole finding food to eat and water to drink is really, really hard, but the hardest thing of all…is being all alone. It’s so desperately hard that three years in Chuck considers killing himself. In the end he decides to stay alive, aided by the presence of a volleyball that washed up on shore, whom he calls Wilson.

Wilson becomes Chuck’s salvation, a symbolic human that helps him remember his fiancé back at home and keep summoning the courage it takes to hope for rescue. In one particularly gut-wrenching scene, Chuck is having a heated conversation with Wilson the volleyball in which he’s trying to explain why he decided not to kill himself. Apparently Wilson is wondering if they should keep hoping. We only hear Chuck’s side of the conversation, of course, because, well, Wilson is a volleyball, but as the conversation gets more and more intense finally Chuck yells at Wilson: “And what is your point? Well, we might just make it…did that thought ever cross your brain? Well, regardless…I would rather take my chance out there on the ocean than stay here and die on this shithole island spending the rest of my life talking to a goddamn volleyball!”

Then, Chuck picks Wilson up and throws him into the ocean.

In that moment, with Wilson gone, Chuck realizes that now he’s really, really alone, a situation that is completely and totally…hopeless. (You need Kleenex for this part, because Tom Hanks is such a good actor you can feel in that moment all the desperation he was feeling at having lost any sense of community.)

Based on what we read from Jeremiah today, Jeremiah’s feeling much the same way Chuck does, and without even a volleyball with which to converse. The thing is, he’s been sent by God to bring a message of utter destruction to the people. And while the people knew that God got mad at them from time to time, the prevailing thought in the society in which Jeremiah preached his message was undergirded by two unshakable beliefs: first, everyone believed that, no matter what, if they repented God would relent and not bring disaster. And second: everyone was absolutely convinced that the city of Jerusalem and the temple especially would never be destroyed. Never.

Still, Jeremiah persisted in his unpopular message: “The land shall be a desolation!” People! Listen UP! God is going to wipe this place out if you don’t shape up!

Can you hear the crickets?

It seemed as if nobody was listening. Nobody cared what he had to say. Nobody. Jeremiah felt all alone. And so you can hear the desperation in his voice here. Because sometimes when you tell the truth about something, when you buck convention and push back at the status quo, one of the things that can cost you is…community, being part of the crowd. You end up feeling like you’re the only one out there who feels the way you do. You begin to doubt yourself: your calling and your message. With nobody behind you, you feel completely vulnerable and scared. All alone. This is the price Jeremiah paid to tell the truth.

We spoke last week about finding the truth you are called to tell, so having found that, you might know better than I do when it is you feel most alone. But I got to thinking a bit about church as an example. Going to church. Especially our church, where you get prodded all the time to invest, get involved, to commit.

But everybody in my circles these days is talking about the decline and complete irrelevance of the institutional church. Studies have shown that there’s no doubt whatsoever: the institutional church is shrinking in numbers. Churches are closing all over the place. Many people find communities of faith irrelevant. Just the other day I was talking to someone I’d just met the other day and he began to ask me about church like it was a completely foreign concept to him. Because it was, I realized. We talked for awhile about our community here at Calvary and all of you who invest your lives here. Finally he looked at me with confusion and asked, “But how do you get people to SHOW UP?”

I think of this sometimes when I think about so many of you, about what it takes to come to church, to invest your life in a community like this one, to even to admit out loud that you think there might be a God, or to live your life in such a way that it looks different from a lot of the messages you hear all around you.

I would imagine that this might be one area in which you might feel as Jeremiah felt: all alone. Among your colleagues at work, among your group of friends, maybe even within your families…there very well may be a whole bunch of people looking at your commitment to faith and faith community, scratching their heads in confusion, or talking about you behind your back. And that has to feel rather, well, lonely from time to time. Maybe even a bit what it felt like to be the prophet Jeremiah.

Our Gospel lesson today is a very familiar story of a shepherd who leaves 99 sheep to go out and search for the one sheep of his who has managed to wander off, lost. The way this has been told and interpreted in most church settings is that the lost sheep represents sinners—those who have wandered from a right path. You know we sing it: “Jesus sought me but a stranger wandering from the fold of God…”.

But I wondered as I read Jeremiah’s deep loneliness and despair, I started to think about Jesus’ parable in a new way. Because I think it’s the nature of God to seek us out, no matter who we are, over and over again, to draw us back into community and relationship. It could be because we’re sinners in need of grace like the tax collectors in Luke’s gospel today. And it could be because sometimes we feel all alone when we tell the truth we’re called to tell. Could it be that God seeks us out to sustain us in the hard task of answering the call to tell the truth, to live in unconventional ways that fly in the face of society around us?

After all, Jesus was not ignorant of what it was going to mean for him and his disciples to preach the message he’d come to teach them. They were going to face opposition; people wouldn’t believe them. They’d feel desperately alone, and many of them would die alone for the truth they were called to tell. I wonder if they ever, in those loneliest moments, held in their minds that image of God as shepherd, coming to them and gathering them up, being there with them and giving them hope and courage and the conviction that they were not, in fact, alone. Because Jeremiah wasn’t really alone; there were people who listened to what he said and shaped up. And we’re not alone either. We’re just called, called to tell the truth, even when it costs us.

You probably know how Cast Away ends. The day after Chuck’s contentious exchange with Wilson, part of a port-a-potty washes up on the shore of his island. With significant ingenuity Chuck manages to build a raft and make that port-a-potty into a sail, all the while discussing his plans with Wilson. And then one day he pushes off, out into the ocean, where he’s finally rescued. The memory of his fiancé keeps Chuck going; the thought of being reunited with her becomes his sole focus.

When he gets home he finds she’s moved on. She had to: he’d been gone and presumed dead for so many years. So Chuck finds himself surrounded by all kinds of people yet, again, strangely alone. And again, somehow, he finds the courage to keep going. “I know what I have to do now. I have to keep breathing. Because tomorrow the sun will rise. And who knows what the tide could bring?”

People of faith, telling the truth in a world that doesn’t want to hear it can leave you feeling desperately lonely some days. Hear the word of hope that the prophet Jeremiah had such a very hard time hearing: you are not alone.

So keep breathing. Tell the truth you’re called to tell. Because tomorrow the sun will rise. And who knows what the tide could bring?

Amen.

[1] Walter Brueggemann, “The Book of Jeremiah: Portrait of the Prophet,” in Interpreting the Prophets, ed. J.L. Mays and P.J. Achtemeier (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987), 117-18.