Sunday, September 8, 2013

Sixteenth Sunday after Pentecost

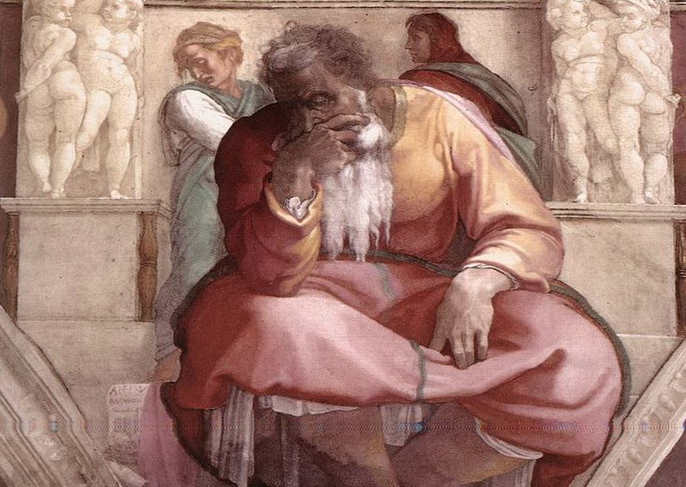

Jeremiah 18:1-11

Rev. Dr. Amy Butler

_____________________________

An introduction to Jeremiah, modified from The Message:

“Imagine there was one guy on board the Titanic with sonar equipment trying to get the captain and crew to believe there was an iceberg ahead. They’d never heard of sonar and thought he was nuts. That guy was Jeremiah, and the Titanic was his country.

Jeremiah’s troubled life spanned one of the most troublesome periods in Hebrew history, the decades leading up to the fall of Jerusalem in 587 BC, followed by the Babylonian exile. Everything that could do wrong did go wrong. And Jeremiah was in the middle of all of it, sticking it out, praying and preaching, suffering and striving, writing and believing. He lived through crushing storms of hostility and furies of bitter doubt. Every muscle in his body was stretched to the limit by fatigue; every though in his mind was subjected to questioning; every feeling in his heart was put through fires of ridicule.

In a way, Jeremiah was a failure because he didn’t achieve the results he wanted. In a way, Jeremiah was a success, because he had the courage to tell the truth.”

Perhaps you know the story from ancient Greek history of Pheidippides.

Pheidippides was a soldier in the Athenian army during the First Persian War. You’ll, naturally, recall that the First Persian War happened about 2,500 years ago. And 2,500 years is a long time to be remembered; here’s what Pheidippides did. The Greeks were in a war with the Persians, who were systematically conquering much of the ancient world and had their sights set on Greece.

So in 490 BC the Persian army sailed the Aegean Sea toward Greece with the aim of conquering Athens. When they landed the Persians were met on the Plain of Marathon by the Athenian army.

Though they were fierce and well armored, the Athenian army was about half the size of the Persian army.

The Greeks knew about this disparity at the outset, so back in Athens folks were battening down the hatches, pretty sure that their city was about to be sacked. Here’s the thing, though. The Athenian army managed to pull off a sneaky move in which they surrounded the Persians and defeated them.

Once the Persians figured out they weren’t going to get to Athens over land, they got back in their boats and headed to Athens by water.

The Athenian army was panicked; they thought for sure if the Persians showed up in Athens the city leaders would assume the battle had been lost and surrender the city before the army could get back.

The Greek army commanders’ thought was that if the city knew of the victory and heard the news that the army was on its way back, leaders in Athens could probably hold out until the army got there. And that’s where Pheidippides comes in.

As the story goes, army commanders chose Pheidippides to run to Athens with the message, and run he did, with this urgent message over 26 miles, all the way back to Athens without stopping, desperate to get to the city with the news of the win before the Persians did. Pheidippides did, in fact beat the Persian army to Athens. Upon reaching the city he burst into the assembly and announced “We have won!” at which time he collapsed and died.

This is the story from which we get the modern marathon, of course. It also illustrates a basic truth of human life that I myself have suspected for some time: that is, running is bad for you.

Actually, I begin the sermon this morning with the story of Pheidippides because he was someone who had an urgent message to deliver, and the delivery of that message cost him. And the same was true of the prophet Jeremiah, whose writings appear as our Hebrew lectionary texts for the next four weeks. Over these next few weeks we’re going to learn a lot about the prophet Jeremiah.

You heard a bit of Jeremiah’s background earlier in the service today, but just to review—particularly since we spent the summer learning about the history of the Israelites during the time of the judges. Well, after the judges the Hebrew people got what they wanted: a king. And there’s lots of intrigue in the story of Israel’s monarchy, but by the time we get to the life of Jeremiah the era of the monarchy is quickly coming to an end, and things are in pretty severe crisis.

During this time in Hebrew history there were spiritual figures called prophets who were sent to the people and their leadership to bring messages from God. We still think of a prophet in much the same way they were understood then. Walter Brueggemann describes the work of the prophet this way: prophets were called by God “to have an impact on persons, to impinge upon perception and awareness, to intrude upon public policy, and to evoke faithful and transformed behavior.”[1]

No pressure or anything.

So Jeremiah the prophet lived in the decades leading up to, during, and after the fall of Jerusalem, when the Hebrew people were taken into exile in Babylon. Jeremiah’s prophetic career was exceptionally long, spanning the reigns of five kings. For years and years and years Jeremiah preached his message. And in the end, he did not, in fact, manage to influence perception, policy or behavior very much at all. Jeremiah brought the message as he was told by God to bring…and nobody listened. At the end of Jeremiah’s life the future of Israel still hung in the balance; Jeremiah never saw the resolution or restoration God promised.

You could say that he was a failure.

There’s a lot of historical information in the book of Jeremiah, lots to study from a historical perspective. There’s also much to be said about how God is depicted in the book of Jeremiah—we might be able to explore a bit about what God expects from us and how God interacts with us by reading what Jeremiah wrote.

There’s a lot of historical information in the book of Jeremiah, lots to study from a historical perspective. There’s also much to be said about how God is depicted in the book of Jeremiah—we might be able to explore a bit about what God expects from us and how God interacts with us by reading what Jeremiah wrote.

But instead of looking at our texts through these lenses, for the next four weeks we’ll be taking a close look at the cost of being a prophet—the toll it takes on a life to tell the truth.

The prophet Jeremiah is unusual among biblical prophets in that we get a glimpse into what it personally cost him to bring the message God told him to bring—trial, arrest, ridicule, imprisonment…a broken heart. Because the thing is: if a prophet does his job well, not too many people like him.

Actually, dislike is probably too mild of a term. People often hate prophets, because the message they preach and the ardent and upsetting way in which they do it cause dis-ease. Good prophets will make people uncomfortable, sometimes so uncomfortable that we kill these prophets, just to make them shut up.

So, we begin to learn about Jeremiah today in a passage where he is told by God to go down to the potter’s house. The potter’s house in Jeremiah’s day was a place you’d go to acquire various containers needed for daily living—like the hardware store. So Jeremiah went to the potter’s house and watched the potter work and rework the clay. When it didn’t conform to the shape he wanted the potter would destroy what he was making and start again…over and over until the pot turned out the way he’d wanted.

As Jeremiah watched the potter work, he heard the message God wanted him to bring to the people. Basically, God said: look at the potter and watch what he does with the clay. Now you go and tell the people that I am just like a potter. And if you don’t turn from your evil ways, I will do to you exactly what that potter did to that clay. Destroy; start again.

So, with that, Jeremiah was given his mandate…a message who’s delivery would cost him, big time. This was no soft and tender devotional invitation from God—as we happen to sing it in the hymn we just sang. Oh no, this is a harsh warning to shape up or else…and Jeremiah got the lucky job of passing that message along.

This particular message given to Jeremiah in the potter’s house was not unlike the other messages God told him to share with the people, messages that contained, over and over and over again, cheery words like: sword, famine, pestilence, death, destruction, break, scatter, waste, ruin, desolation….

And the message he was called to tell was reflected in his own life: as he answered God’s call to proclaim the truth he himself was broken and put back together over and over again—in fact, we call him the Weeping Prophet.

So why would he do it? What would Jeremiah pay such a steep personal price to do something that was unpopular, distasteful, and painful?

I think the answer is: he couldn’t not do it. He felt a call—the call of God—to do what God intended for his life. And he knew that running away from that compelling call would be worse than courageously answering it.

I recently read an article on the Huffington Post entitled: “A Warning to Young People: Don’t Become a Teacher.”[2] The article was written by a teacher who says that teachers these days are more stressed and less valued than any other time in history. With public criticism from politicians, incredible administrative pressure to meet standardized testing levels, increasingly diminishing compensation incentives like reasonable salaries, tenure opportunities, and pension contributions, the price you pay to enter the teaching profession these days is pretty steep.

The author doesn’t sugar coat realities. But as I read the article I could hear the wistfulness in his words. He talked about the incredible satisfaction he got from working with students, the rich reward of watching them discover talents and learn new skills as the direct result of his guidance in the classroom. While his article warned young people to avoid teaching at all costs, the truth is: in the end he was still teaching—and after 14 years earning, he said $37,000 a year…because he couldn’t not teach. It is his life’s calling.

And such was where the cost began for the prophet Jeremiah. His message was harsh; he didn’t see results. But in his life there was a compelling call, it was something he could not ignore. Telling the truth to God’s people began with being truthful with himself. Other aspirations fell to the wayside as he lived a life sold out to the commitment of telling the truth when nobody else would.

And what does this have to do with you and me? Just like the prophets of old, we live in a world where it’s usually most expeditious to maintain the status quo, to avoid the hard conversations, to choose a course that will get us the things most valued in our society: money, position, prestige.

But there are many truths that need to be told in this world, and not enough truth-tellers to tell them.

As people created in the image of God, I feel sure that each one of us has a call to answer, a truth to tell. We may suppress that or ignore it or try to drown it out with any number of other things, but it’s there.

And answering whatever that call may be in your life could, like Jeremiah, cost you a lot: relationships, status, even material things.

But not answering that compelling call to tell the truth might cost even more.

So, we begin today by hearing the call of God to Jeremiah as a challenge for us to be honest with ourselves about the truth we’re being called to tell, and to ask ourselves the question: will we tell it?

Amen.

[1] Walter Brueggemann, “The Book of Jeremiah: Portrait of the Prophet,” in Interpreting the Prophets, ed. J.L. Mays and P.J. Achtemeier (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987), 117-18.